Our mission and impact

What we stand for and how we got here

Our mission, vision, and values

Riverkeeper protects and restores the Hudson River from source to sea and safeguards drinking water supplies, through advocacy rooted in community partnerships, science and law

Guarding your waterways

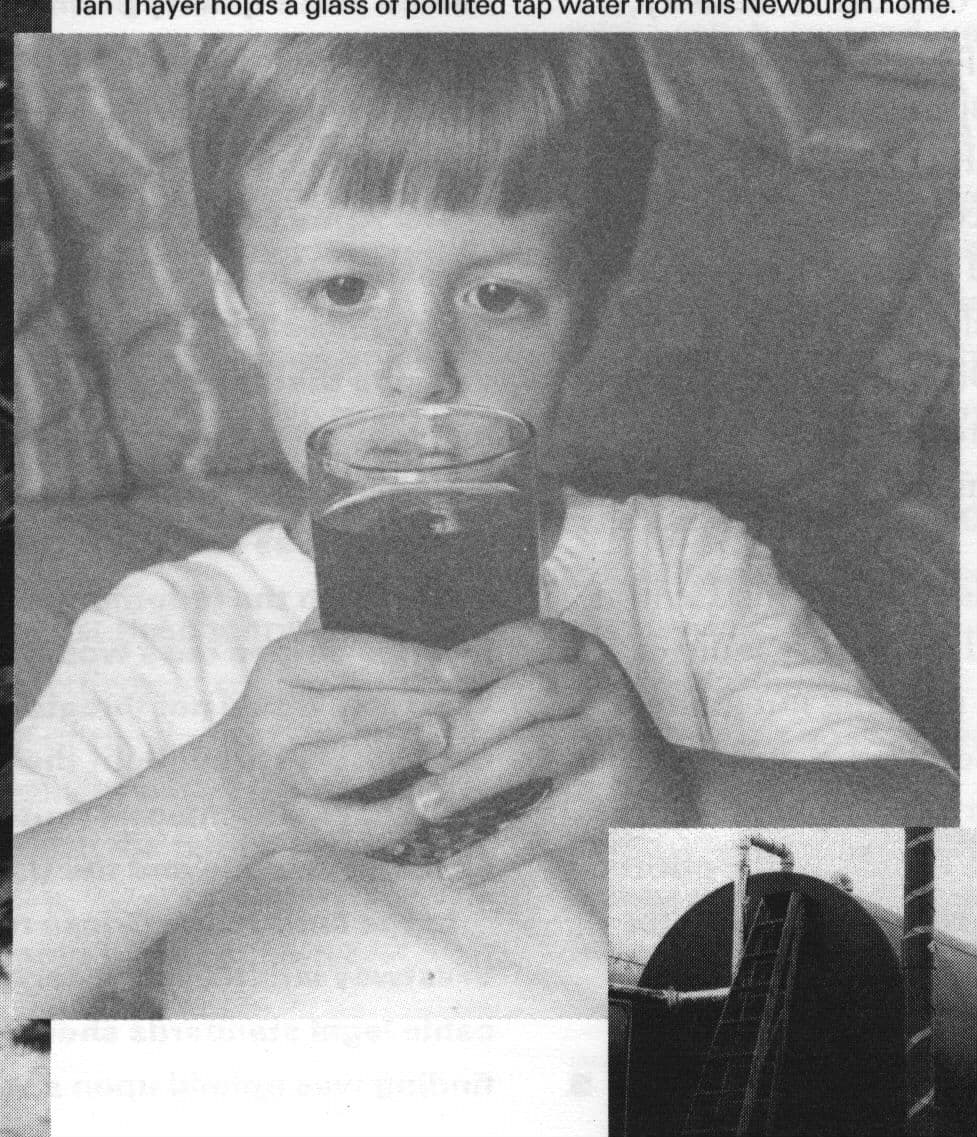

Defending clean drinking water

Finding solutions

Riverkeeper's core values

- the fundamental rights of the Hudson River, its tributaries, and all the living things that depend upon them to exist and thrive in healthy, balanced ecosystems,

- clean water as essential to all living things and access to clean drinking water as a human right,

- a reduction of environmental harms, especially for disproportionately impacted communities and decimated fish and wildlife populations,

- facts, science, and community voices as the foundation of our work,

- trust, respect, integrity, and justice as the basis for our relationships, both within and beyond our organization, and

- environmental and recreational benefits for all.

Riverkeeper's vision

- restored to ecological health and balance,

- free-flowing, resilient, and teeming with life,

- reliable sources of safe, clean drinking water,

- recovered from historic and inequitable environmental harms,

- safe and accessible for swimming, fishing, boating and other recreational activities, and

- valued and stewarded by all.

Riverkeeper's Strategic Plan

Our story

Looking to the future

Our history

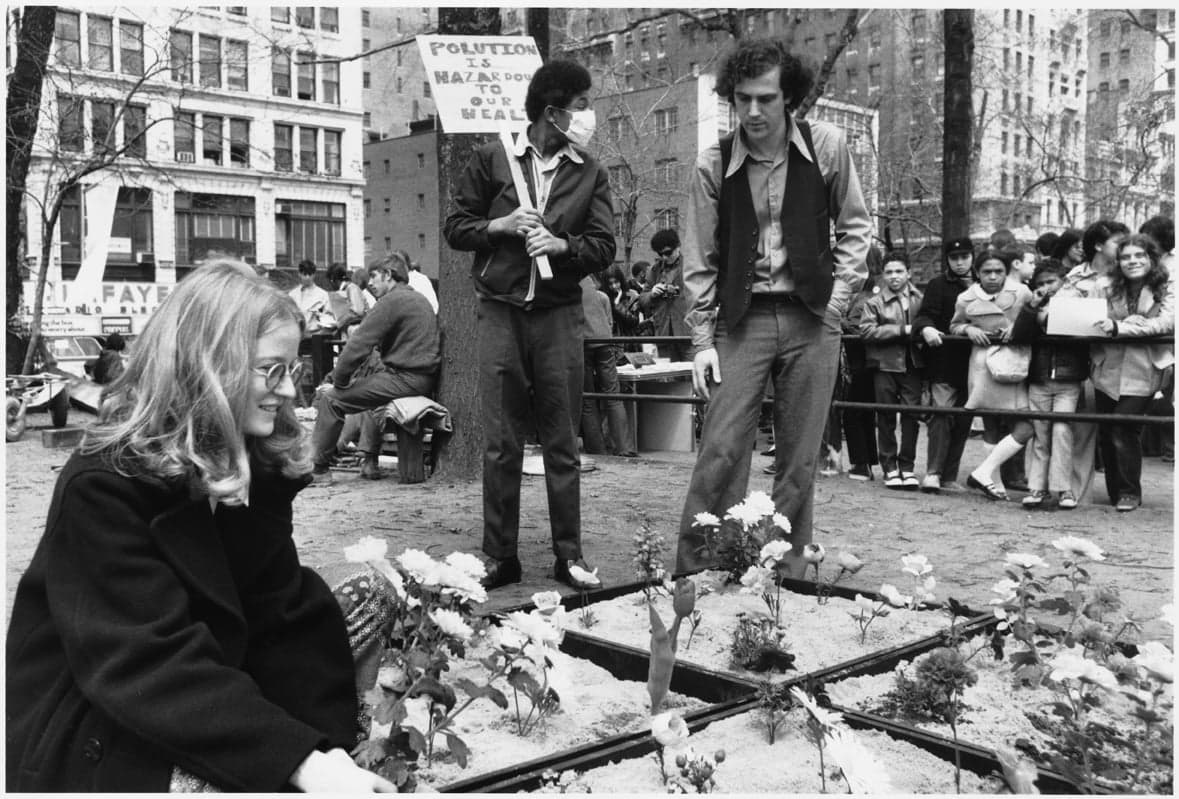

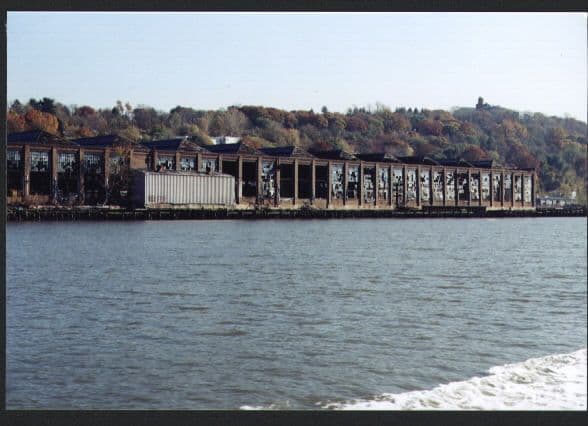

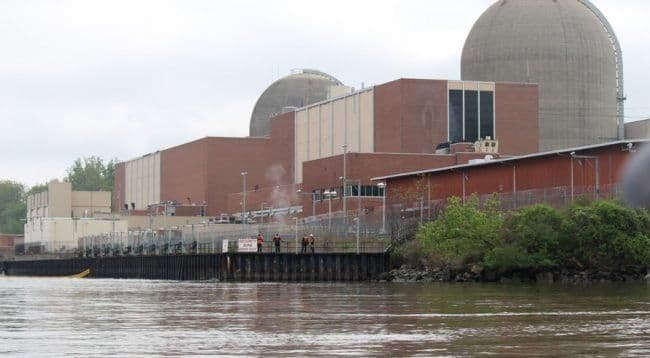

The Hudson, condemned as an “open sewer” in the 1960s, is today one of the richest water bodies on earth. How did we get from there to now?

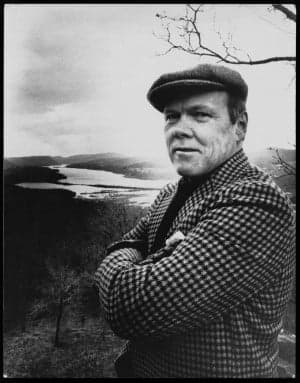

Photo: Evelyn Floret for Sports Illustrated

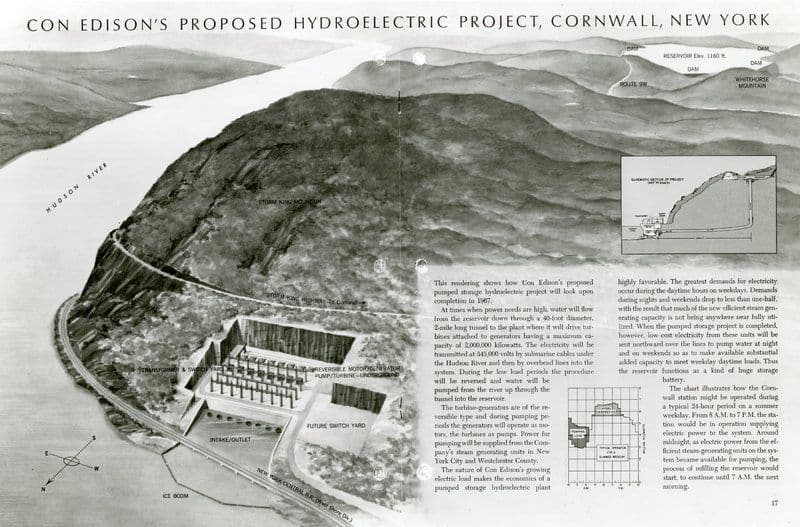

Fight against Storm King plant

Join the fight for clean water

Riverkeeper’s work is only possible because of support from people like you who care about the Hudson and the communities that rely on it.

2400+

miles of river patrolled and sampled by Riverkeeper boats annually, from the Upper Hudson and Mohawk River all the way to New York Harbor

404

tons of debris removed from the river by thousands of Riverkeeper volunteers since 2012

$5.5B

$5.5 billion for clean water allocated since 2017 from New York State thanks to our advocacy work

28,148

letters to lawmakers and decision makers in one year